Key Findings

- Following the 2018 South Dakota v. WayfairSouth Dakota v. Wayfair was a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision eliminating the requirement that a seller have physical presence in the taxing state to be able to collect and remit sales taxes to that state. It expanded states’ abilities to collect sales taxes from e-commerce and other remote transactions. U.S. Supreme Court decision eliminating the physical presence standard for sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. nexus, 43 of 45 states with statewide sales taxes have adopted collection and remittance obligations for remote sellers, and 38 have implemented marketplace facilitator regimes.

- Safe harbors for small sellers help avoid imposing constitutionally suspect undue burdens on remote sellers; they should take the size of the state’s economy into consideration, be denominated in gross sales (not transactions), be calculated under the state’s own tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , and be designed to avoid “notch effects” where exceeding the safe harbor imposes a retroactive obligation on prior transactions.

- Unity and uniformity are vital for a sound, constitutionally valid remote sales taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. regime; while local sales taxes are entirely consistent with Wayfair, all jurisdictions in a state should use the same sales tax base, with a single point of administration.

- Simplified Seller Use Taxes, like those adopted in Alabama and Louisiana, try to address one constitutional concern (undue burden) by substituting another (discriminatory taxation), in some cases imposing higher rates on remote sellers than are faced by in-state merchants.

- States should provide free software and lookup tools that can be used directly or integrated with vendor solutions to enable sellers to determine the appropriate jurisdiction and applicable rate for each remote sale

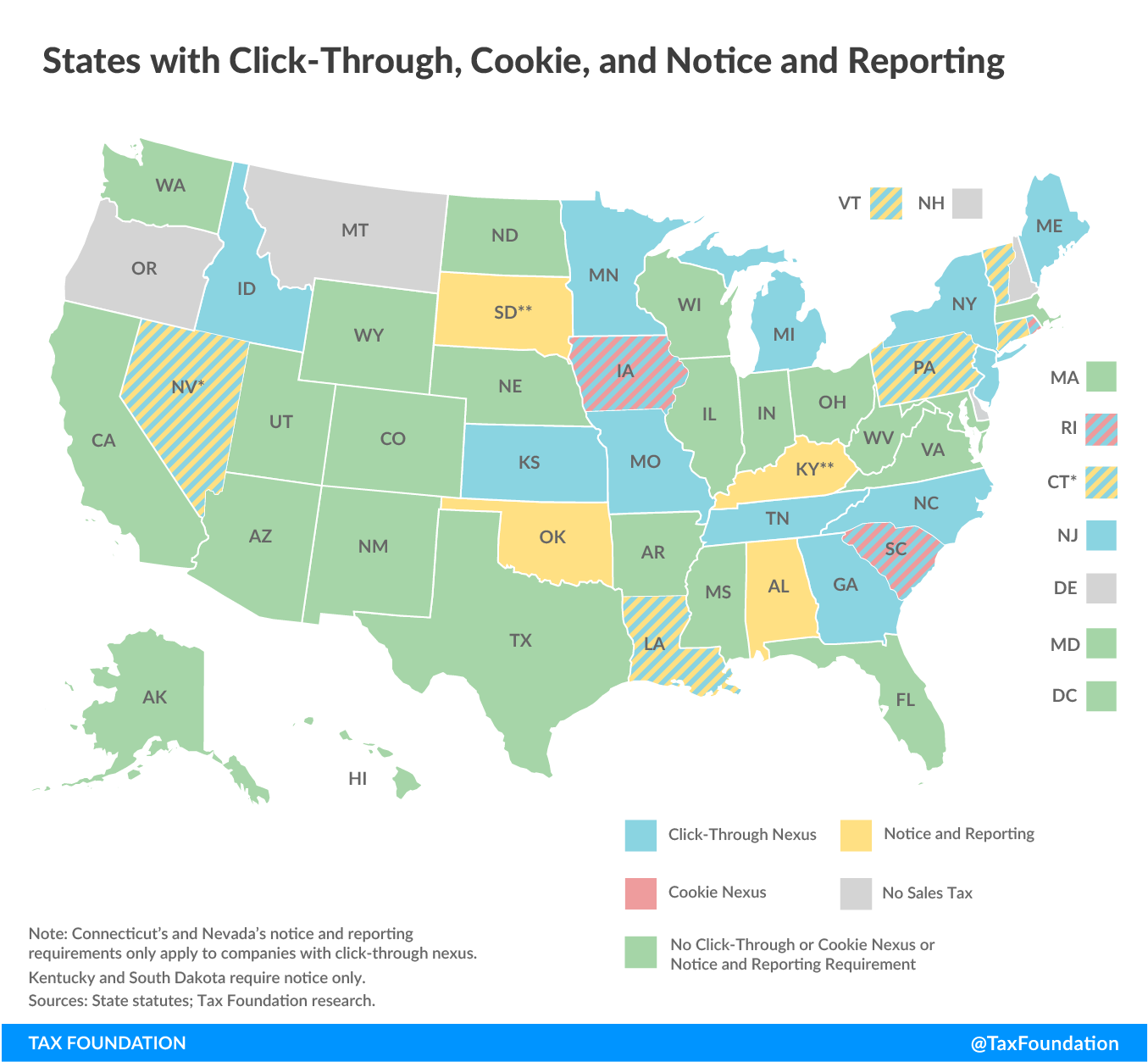

- Prior to Wayfair’s endorsement of an economic presence standard, states found creative, if sometimes dubious, ways to expand the definition of physical presence, like click-through or cookie nexus, or notice and reporting requirements for remote sellers; now that states have a more straightforward way to impose sales tax obligations, they should repeal these subjectively-enforced vestiges of the prior regime.

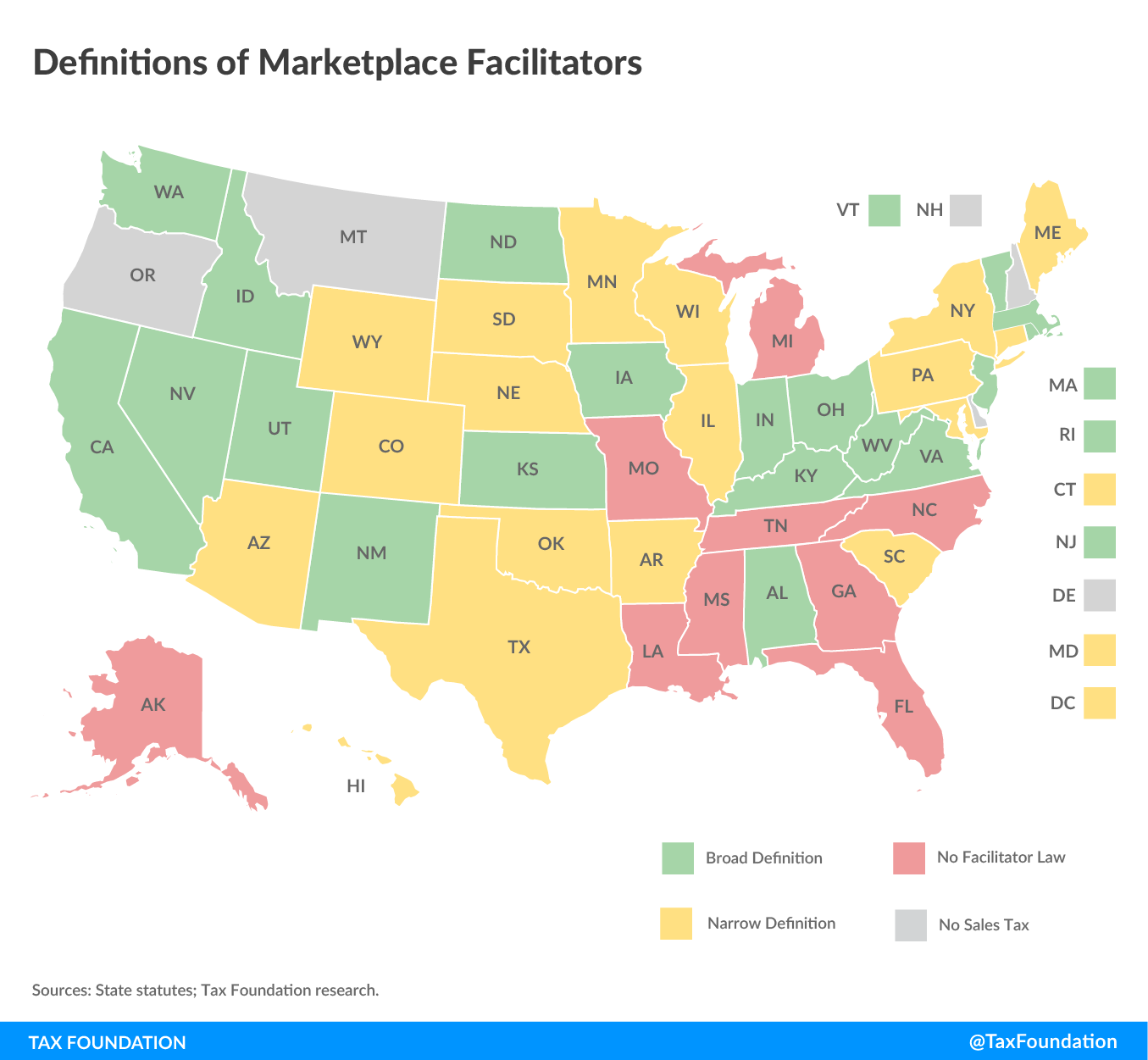

- Most states have adopted marketplace facilitator laws which shift tax collection obligations from sellers in a marketplace to the company facilitating the sale

- States must ensure that their definition of facilitators is not excessively broad, capturing service providers with no reasonable way of collecting the tax or resulting in double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. , and should offer sellers and facilitators a way to contractually agree for the seller to retain collection responsibility where they are better situated to do so.

- The 10 states which use destination sourcing for out-of-state sellers but origin sourcing for some or all intrastate sales should prioritize adopting destination sourcing for all sales, as should the two states which, while more internally consistent, use origin sourcing for all sales.

- The contours of jurisprudence governing remote seller and marketplace requirements remain ill-defined, but nexus standards under both the Due Process and Dormant Commerce Clauses, along with prohibitions on undue burdens on, or discrimination against, interstate commerce, provide important guidance for states as they continue to refine their post-Wayfair sales and use tax codes.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Brief History of Remote Sales Tax Authority

- Current State of Remote Seller and Marketplace Facilitator Requirements

- Providing Adequate Safe Harbors

- Avoiding Notch Effects

- Embracing Sales Tax Unity and Uniformity

- Providing Look-Up Software and Payment Portals

- Moving Past Physical Presence (Click-Through & Cookie Nexus, Notice and Reporting)

- Marketplace Facilitator Laws

- Navigating the Law Around Remote Sales Tax Collections

- Conclusion

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeIntroduction

Just as the analog era gave way to the digital, the Quill era yielded to the Wayfair era. Tax provisions are discussed as pre- or post-Wayfair as if the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision served as a dating convention, and in a way it does. Within a year of the June 2018 decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair,[1] nearly every state had adopted laws and regulations taking advantage of the newfound authority to tax remote sales in which the seller lacked physical presence, with most following those up with the implementation of tax regimes obligating marketplace facilitators (entities that do not sell goods directly but provide a platform for sellers) to collect and remit taxes on remote sales on behalf of their sellers. Although states have almost invariably adopted new post-Wayfair tax regimes, artifacts of the prior era remain embedded in the tax code—fossils now, but not without consequence. And the hasty actions in the dawning of the Wayfair era are now being revisited in the clear light of day.

This paper explores the choices states have made heading into calendar year 2020: the safe harbors they have adopted for small sellers, software and lookup tools made available to remote sellers, simplifications made to the tax structure, uniformity provisions, the continued existence of extensions of physical presence like click-through or cookie nexus, the definitions adopted for marketplace facilitators, and solutions to the “notch effect” generated with the first transaction above the state’s safe harbor, among others. It also outlines legal pitfalls states should seek to avoid and offers up a few best practices for designing reliable, equitable, legally-sound remote sales tax regimes.

Figure 1.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeEven a year and a half after the Supreme Court’s decision, state policies remain in flux. The Multistate Tax Commission (MTC)’s working group on Wayfair implementation and marketplace facilitator laws is still meeting, and issued a white paper in December 2019 sketching the ongoing debate about the design of post-Wayfair laws and regulations.[2] The State and Local Tax Task Force of the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) reported model marketplace facilitator legislation to the full executive committee in late November.[3]

Many states justly see the provisions adopted in 2018 as temporary, to be amended or replaced once there has been time for greater scrutiny of the complex issues arising from Wayfair implementation regimes. It is all too easy, however, to unearth “temporary” laws from the past that are now preserved in amber; tax codes are littered with such provisions. It is, therefore, incumbent upon states to see their post-Wayfair laws as a work in progress. By facilitating a comparison of provisions and practices across states and highlighting best practices, this paper is intended to help inform that process, and to serve as a reference for those seeking to understand the remote sales tax landscape entering the year 2020.

A (Very) Brief History of Remote Sales Tax Authority

When a narrowly divided U.S. Supreme Court overturned the physical presence standard established in two earlier cases, National Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Illinois Department of Revenue (1967) and Quill Corp. v. North Dakota (1992), it created the second seismic shift in state taxation in less than half a year, following the December 2017 enactment of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which also had significant implications for state tax bases. Considered alone, either event could have represented a generational change; together, they altered the landscape of state taxation dramatically.

The Court’s 5-4 alignment in Wayfair understates the consensus that existed on the key point at issue, that Quill was wrongly decided, not just in light of recent developments, but even on its own terms.[4] Over half a century ago, in National Bellas Hess, the Court concluded on both Due Process Clause and Commerce Clause grounds that only a business with property or payroll in a state had the minimum contacts necessary to permit states to impose sales tax collections and remittance obligations.[5] In 1992, the Quill Court sought to situate this requirement entirely within the Commerce Clause, which was fortuitous—some would say conveniently so—for those favoring a federal legislative framework for remote sales tax collections, since Congress has the power to intervene in Commerce Clause questions, but cannot override due process protections.[6]

Congress, however, was not prepared to act; federal lawmakers tend to be reticent to interject themselves into such questions of state authority. Meanwhile, states became progressively more creative in defining physical presence for tax purposes, increasingly determining that contacts as tenuous as placing a “cookie” on the computer of someone in the taxing state was sufficient, as if a few bits and bytes constituted establishing a physical presence in the state.[7] They implemented “affiliate nexus” and imposed notice and reporting requirements on remote sellers they lacked authority to tax outright.[8] Quill was still in effect, but its bright-line rule was giving way to a blurred line as states adopted any available expedient to require, at very least, the major online retailers to collect and remit sales taxes.

This state of affairs pleased no one: not the states, which would have preferred something more robust, nor retailers, which had to comply with nebulous and conflicting standards. But overturning decades of precedent—even getting the Supreme Court to contemplate the idea—is not easy. Then came 2015, when Justice Kennedy wrote separately in a case regarding Colorado’s notice and reporting requirements that “[t]he legal system should find an appropriate case for this Court to reexamine Quill and Bellas Hess.”[9] It is not often that a justice of the Supreme Court, one who was in the Quill majority no less, actively solicits an opportunity to overturn existing case law, and the states took notice.

Before the ink was dry on the Wayfair decision, states began moving forward with responsive legislation; a few, indeed, had already adopted economic presence laws anticipatorily. Shortly thereafter came the marketplace facilitator laws, shifting collection and remittance requirements to platforms for sales facilitated by a third party, like eBay, Etsy, or Amazon Marketplace.

The Wayfair decision, then, was the culmination of decades of tension between state laws and constitutional constraints, and the opinion, written by Justice Kennedy, answered one key question to the states’ liking—sufficient nexus for tax purposes can be established in the absence of physical presence—while leaving many others unresolved. The Court’s decision to make favorable reference to certain salutary features of the challenged South Dakota law (written for the express purpose of serving as a vehicle for a Quill challenge)[10] provides states with important guidance in developing their own remote sales tax frameworks, and further insight can be gleaned when reading that dicta in light of the Court’s holdings in related tax cases. This is particularly important because the creativity states exhibited in developing workarounds to the old physical presence standard has not yet abated.

There are, however, clear advantages to following what we and others have termed the “Wayfair Checklist,”[11] and to resolving technical questions for remote sales tax and marketplace facilitator laws in keeping with nationally favored best practices. A measured approach helps insulate states from legal challenges, enhances compliance, and reduces administrative costs, all benefits to the taxing authorities, in addition to offering simplicity and certainty for remote sellers, including smaller sellers that may otherwise find compliance excessively costly and burdensome.

To this end, we explore several pertinent design choices within remote sales tax and marketplace facilitator laws, suggesting optimal approaches, sketching out the legal considerations, and delineating current state approaches, before delving into a more detailed consideration of the legal questions that remain unresolved as states test the limits of the post-Wayfair era of taxation.

The Current State of Remote Seller and Marketplace Facilitator Requirements

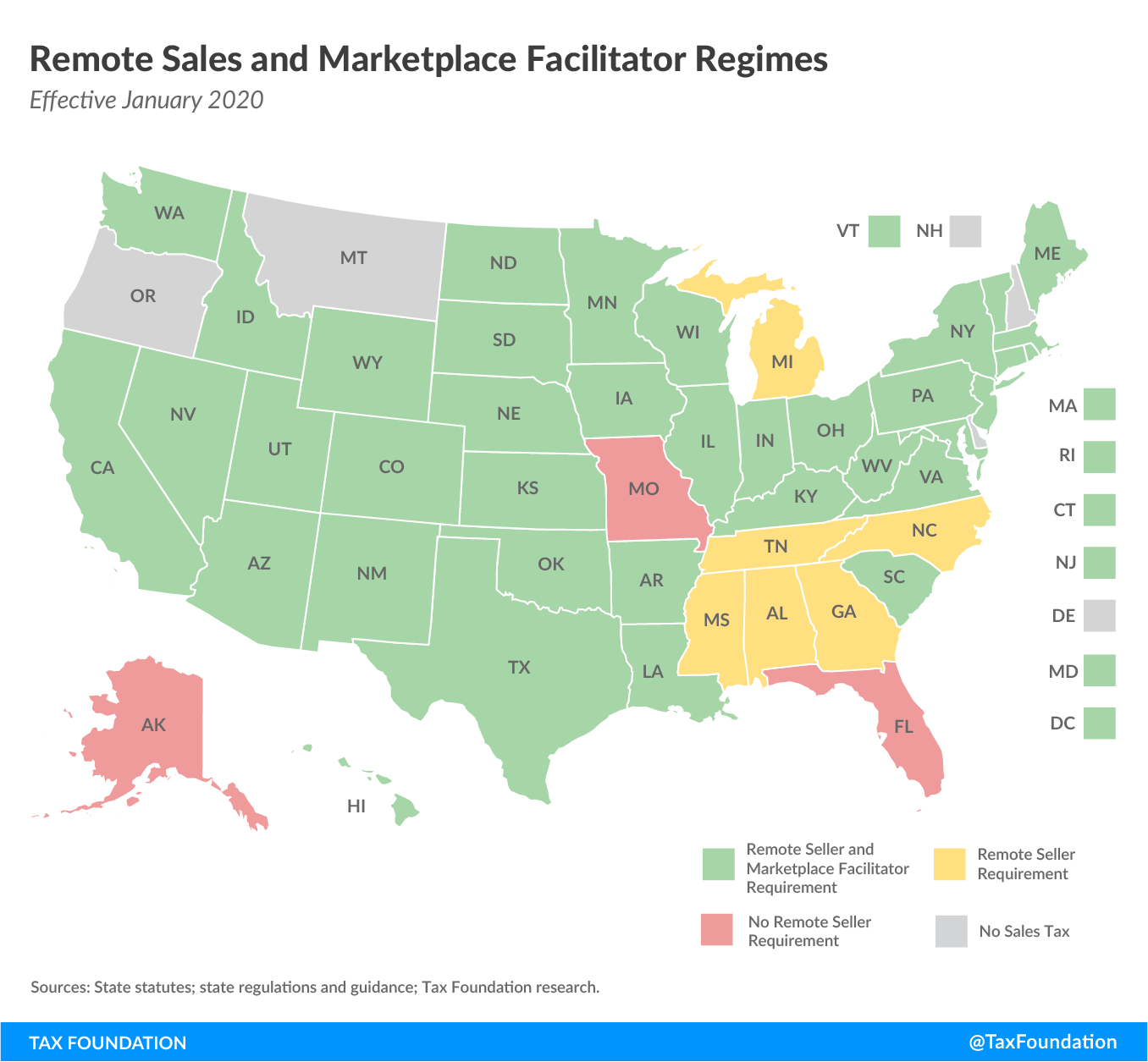

As of January 2020, 43 of the 45 states with statewide sales taxes[12] will have adopted collection and remittance obligations for remote sellers, and 38 will have implemented marketplace facilitator regimes. In most cases, these new systems were adopted legislatively, but in a handful of states they are wholly the consequence of administrative guidance or regulations.

|

Sources: State statutes; regulations and guidance; Tax Foundation research. |

||||||

| Remote Seller | Marketplace Facilitator | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Imposition | Statutory | Regulatory | Imposition | Statutory | Regulatory |

| Alabama | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Alaska | ||||||

| Arizona | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Arkansas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| California | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Colorado | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Connecticut | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Delaware | No sales tax | |||||

| Florida | ||||||

| Georgia | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Hawaii | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Idaho | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Illinois | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Indiana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kansas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kentucky | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Louisiana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Maine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Maryland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Massachusetts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Michigan | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Minnesota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mississippi | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Missouri | ||||||

| Montana | No sales tax | |||||

| Nebraska | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Nevada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | |||||

| New Jersey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| New Mexico | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| New York | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| North Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| North Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ohio | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Oklahoma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Oregon | No sales tax | |||||

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rhode Island | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| South Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| South Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Tennessee | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Texas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Utah | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Vermont | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Washington | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| West Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Wisconsin | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Wyoming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| District of Columbia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

States which have proceeded administratively have largely justified this action on existing statutes that contemplate the imposition of sales and use tax collections on all sellers, limited not by state statute but by a series of prior judicial decisions. Therefore, these states view the Wayfair decision as permission to enforce their existing laws. This is, however, dubious reasoning, as Wayfair-compliant remote sales tax regimes are characterized by provisions not fully anticipated by laws already on the books, necessitating a significant amount of rulemaking—regarding safe harbors, for instance, or the definition of marketplace facilitators—that is best accomplished legislatively.

In Kansas, where negotiations between the legislative and executive branch broke down, the Department of Revenue promulgated a requirement with no safe harbor for small sellers on the grounds that nothing in the existing statute authorized such a provision.[13] This approach may be on a collision course with the federal judiciary, but Kansas authorities do have a point: creating a new regime for Wayfair-compliant remote sales tax collections without specific authorizing legislation is an aggressive assertion of executive power and leaves the state’s system on shaky ground. In at least nine states (Massachusetts, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming), regulations were subsequently codified by the legislature, a step that other states operating on the basis of regulations or guidance should take to heart.

Ironically, Kansas officials did create a marketplace facilitator provision through administrative guidance, even though it clearly was not contemplated by existing law.[14] Kansas is the only state to establish a marketplace facilitator regime administratively, though five states—Kansas as well as Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, and Nevada—currently impose remote sales tax collection and administrative requirements administratively, rather than by statute.

|

n.a.: Not applicable. Sources: State statutes; regulations and guidance; Tax Foundation research. |

||

| State | Remote Seller | Marketplace Facilitator |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 10/1/2018 | 1/1/2019 |

| Alaska | No state sales tax | |

| Arizona | 9/30/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Arkansas | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| California | 4/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Colorado | 6/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Connecticut | 7/1/2019 | 12/1/2018 |

| Delaware | No sales tax | |

| Florida | n.a. | n.a. |

| Georgia | 1/1/2019 | n.a. |

| Hawaii | 7/1/2018 | 1/1/2020 |

| Idaho | 6/1/2019 | 6/1/2019 |

| Illinois | 10/1/2018 | 1/1/2020 |

| Indiana | 10/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 |

| Iowa | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Kansas | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Kentucky | 10/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 |

| Louisiana | 7/1/2020 | n.a. |

| Maine | 7/1/2018 | 10/1/2019 |

| Maryland | 10/1/2018 | 10/1/2019 |

| Massachusetts | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Michigan | 10/1/2018 | n.a. |

| Minnesota | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Mississippi | 9/1/2018 | n.a. |

| Missouri | n.a. | n.a. |

| Montana | No sales tax | |

| Nebraska | 1/1/2019 | 4/1/2019 |

| Nevada | 10/1/2018 | 10/1/2019 |

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | |

| New Jersey | 11/1/2018 | 11/1/2018 |

| New Mexico | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| New York | 6/21/2018 | 6/1/2019 |

| North Carolina | 11/1/2018 | |

| North Dakota | 10/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 |

| Ohio | 8/1/2019 | 8/1/2019 |

| Oklahoma | 11/1/2019 | 11/1/2019 |

| Oregon | No sales tax | |

| Pennsylvania | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Rhode Island | 8/17/2017 | 7/1/2019 |

| South Carolina | 11/1/2018 | 4/26/2019 |

| South Dakota | 11/1/2018 | 3/1/2019 |

| Tennessee | 7/1/2019 | n.a. |

| Texas | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Utah | 1/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Vermont | 7/1/2018 | 6/1/2019 |

| Virginia | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Washington | 10/1/2018 | 10/1/2018 |

| West Virginia | 1/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Wisconsin | 10/1/2018 | 1/1/2020 |

| Wyoming | 2/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| District of Columbia | 1/1/2019 | 1/1/2019 |

Essential Considerations for Post-Wayfair Regimes

The Wayfair holding that physical presence is not necessary for nexus does not imply that states can operate with impunity in designing their systems of remote sales tax collections and remittance requirements. States must still mind certain constitutional constraints and should strive to build a straightforward system that keeps the cost of compliance and administration low. In the following pages, we delineate states’ approaches to safe harbors, tax administration, providing seller tools, and other important features, in addition to provisions specific to marketplace facilitator laws.

Providing Adequate Safe Harbors

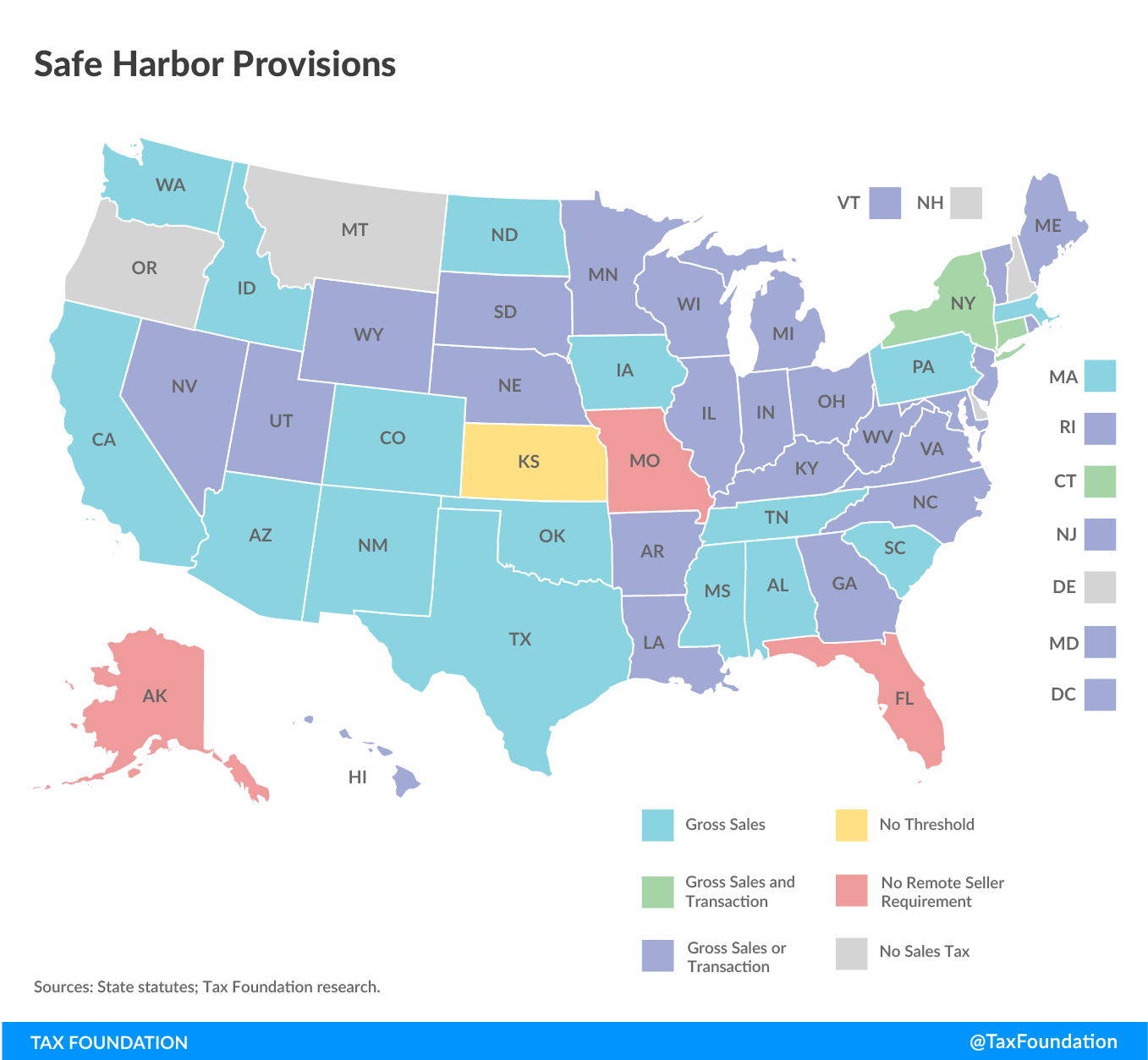

With one notable exception, all states adopting remote sales tax collections regimes post-Wayfair have adopted safe harbors for small sellers. These safe harbors reduce compliance and administrative costs and help ensure that the cost of collecting and remitting the tax will not exceed a company’s net revenue from transactions within the state. They also help insulate states from potential legal challenges, since the lack of a safe harbor—or a poorly designed one—can impose unconstitutional burdens on companies and throw a state’s entire remote sales tax regime into doubt.

A well-designed safe harbor should:

- Take the size of the state’s economy into consideration, with higher de minimis thresholds in larger states;

- Be denominated in gross sales, not transactions, to avoid the possibility of imposing burdens in excess of profits;

- Be calculated using taxable sales under the state’s own sales tax base;

- Avoid “notch effects,” where exceeding the safe harbor imposes a retroactive obligation on already-completed transactions.

For a company to have nexus with a state for tax purposes, it must “avail[] itself of the substantial privilege of carrying on business in that jurisdiction,” meaning that the contacts must not be incidental or unintended. If, for instance, a purchaser walks into a New York art gallery and purchases a sculpture, to be shipped back to her home in Chicago, the gallery in New York undertook no actions in Illinois that might be considered purposeful availment under the Due Process Clause or its cousin within the scope of the Commerce Clause under Wayfair.[15] In addition to availment, there must be “sufficient” economic contacts to establish “substantial” nexus; these contacts cannot be trivial or incidental.[16]

Atop these limitations is a second concern: in exercising their power to tax and to regulate commerce, states must not impose undue burdens on interstate commerce.[17] Exactly how an undue burden analysis would work post-Wayfair is a matter of some dispute,[18] and will be taken up later in this paper, but the Court’s invocation of South Dakota’s safe harbor for small sellers[19] is instructive. There are potentially several ways that a state might impose undue burdens on remote sellers; the lack of some provision to protect small sellers from unreasonably high compliance costs seems to be one of them.[20]

States have almost invariably borrowed the safe harbor concept from the South Dakota legislation to satisfy any legal concerns raised by nexus requirements under the Due Process and Commerce Clauses of the U.S. Constitution,[21] and (separately or subsidiarily) the prohibition on undue burdens. States vary, however, in whether the safe harbor threshold is denominated in gross sales, transactions, or both. South Dakota’s threshold, where nexus attaches with either $100,000 of gross sales or 200 transactions in the state, remains the most common, adopted by 24 states and the District of Columbia, while Georgia uses $250,000 or 200 transactions. Two states (Connecticut and New York) require that both a gross sales and transaction threshold be met, while 17 states rely exclusively on gross sales. Kansas offers no de minimis threshold whatsoever.

| Gross Sales | Gross Sales or Transaction | Gross Sales and Transaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

$100,000 |

CO, ID, IA, MA, ND, NM, OK, PA, SC, WA |

$100,000 or 200 transactions |

AR, HI, IL, IN, KY, LA, MD, ME, MI, MN, NC, NE, NJ, NV, OH, RI, SD, UT, VA, VT, WI, WV, WY |

$100,000 and 200 transactions |

CT |

|

$200,000 |

AZ |

$250,000 or 200 transactions |

GA |

$500,000 and 100 transactions |

NY |

|

$250,000 |

AL, MS | ||||

|

$500,000 |

CA, TN, TX | ||||

|

Source: State statutes; Tax Foundation research. |

|||||

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeA transactions threshold, moreover, introduces complications that are absent from a gross sales standard. Statutes are silent on what constitutes a transaction—an order, a shipment, or an individual item—and even if guidance is provided, the definition of an “item” is no easy matter, particularly if certain items constitute part of a larger whole. A dollar-denominated gross sales threshold better comports with the purpose of the safe harbor and is easier to quantify.Although the gross sales or transaction threshold remains the most common, later adopters have been more likely to rely exclusively on gross sales, which is better policy and more legally sound. A small business might have more than 200 sales into a state worth $5 apiece; in that case, compliance costs can easily outstrip the amount of sales tax collected and remitted, and more importantly, could exceed the company’s profits on those sales, giving rise to claims of undue burden.

Nor should $100,000 be considered the gold standard. Sparsely populated South Dakota accounts for a mere 0.3 percent of personal consumption in the United States; California consumers purchase 48 times as much as those in South Dakota.[22] This is not necessarily to suggest that California’s threshold should be 48 times South Dakota’s ($4.8 million); at some point, the economic contacts are clearly substantial. However, the $100,000 threshold may not be appropriate for all states, and certainly, it is far harder for a small- or mid-sized operation to hit $100,000 in South Dakota sales than it is for them to have $100,000 in sales in a state like California, New York, or Texas, meaning that the same threshold captures smaller remote sellers in those states. Eight states have responded to this concern with thresholds above $100,000, including four (California, New York, Tennessee, and Texas) with $500,000 de minimis thresholds. Other states should follow this approach.

If some states’ safe harbors could create an opening for litigation, Kansas practically invites a lawsuit with the administrative implementation of a remote sales tax regime with no de minimis threshold whatsoever.[23] A single $1 sale would be enough for a remote seller to be required to register with the state and collect and remit sales tax. Kansas’s own Attorney General has argued, in a nonbinding opinion, that the state’s approach is constitutionally suspect:

[W]hile Wayfair did not expressly hold that a statutory “safe harbor” based on value of goods or services sold or number of transactions is required by the Commerce Clause, the Court did rely upon the existence of such a safe harbor in South Dakota’s statute as persuasive evidence that the statute was “clearly sufficient.” It is reasonable to conclude that post-Wayfair, out-of-state retailers whose contacts with a taxing state exceed those approved safe harbor limits may be subject categorically to a duty to collect and remit without offending the Commerce Clause. Similarly, it is reasonable to conclude that the likelihood a state offends the Commerce Clause by imposing a duty to collect and remit on an out-of-state retailer increases the further the retailer’s contacts with the taxing state depart below the “clearly” sufficient safe harbor thresholds.[24]

States should ideally define sales volume with reference to the state’s own sales tax base. A transaction that is exempt from sales tax should not count toward the gross sales threshold, as this can impose substantial burdens on companies with negligible taxable sales. Imagine a small business which sells replacement parts to manufacturers in a tristate area. Perhaps a very small number of consumers also own equipment for personal use, and occasionally place an order directly with this provider, which otherwise almost exclusively trades in untaxed wholesale transactions. If these untaxed wholesale transactions are enough to exceed the safe harbor, then even a single sale to a consumer is enough to require full compliance with the state’s remote sales tax regime—an outcome that makes little sense.

Figure 2.

Avoiding Notch Effects

Seven states and the District of Columbia, either intentionally or by omission in drafting, potentially require a remote seller to collect and remit sales tax for transactions which occurred prior to attaining the state’s threshold for compliance. This is a significant issue (and potentially a constitutional one) for remote sellers, as they never collected sales tax on those transactions in the first place, and have no way to go back to the purchasers and collect it now, meaning that the financial burden for sales tax on prior transactions falls on the retailer, even though the incidence of the tax is normally on the consumer.

In a further wrinkle, because the legal incidence of the sales and use tax is on the consumer, individuals are legally obligated to remit use tax on any taxable transactions on which tax was not collected at the point of sale. While compliance is low—the whole reason why states have been so eager to impose remote collections obligations—some taxpayers do comply with this requirement, creating the possibility that transactions will be double-taxed, with the tax remitted first by the consumer who bought the untaxed good, and then later by the seller after they exceed the safe harbor and are required to remit tax retroactively on prior transactions.

In most cases, this possibility arises from vague statutory language and may not reflect policy intent, in which case a simple amendment could clear up the issue. At least in Hawaii, however, where the state’s unique sales tax—called a general excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. —is levied on the seller rather than merely collected by them from the consumer, retroactivity is clearly the intention, with specific guidance for “catchup income.”[25] Georgia, Idaho, Maine, North Carolina, South Carolina, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia may also have this problem, which is known as a “notch effect,” where an incremental change (one additional sale, in this case) affects the entire system (liability on all prior sales).[26]

Most states avoid this problem either by only taxing sales beginning with the first sale above the threshold, or at some interval after that threshold has been met (future sales), or by requiring collections in a given year based on prior year sales (lookback). Often, both are used.

Notch effects, where they exist, may not only impose undue burdens, but potentially discriminate against interstate commerce. Intriguingly, they also change the nature of a seller’s obligation. Collection and remittance of sales tax is essentially a regulatory requirement; legally, the tax is imposed on the purchaser, and the seller is merely tasked with collecting that tax payment on the state’s behalf at the point of sale.[27] If a seller is obligated to remit sales tax on past transactions, where no such taxes were collected from the purchasers, the seller’s role is transformed from that of the tax collector to that of the taxpayer. Instead of an extension of collections obligations under the state’s longstanding use tax, this begins to look like a new tax levied exclusively on a certain class of out-of-state seller, which is constitutionally fraught. Finally, while the courts have not fully ruled out retroactivity in taxation, the Wayfair court cited South Dakota’s lack of retroactivity as an important point in its favor,[28] and due process concerns arise when sellers lack the knowledge to collect, as is the case if they do not reasonably anticipate exceeding the threshold for compliance.[29]

|

* Kansas imposes collection and remittance obligations beginning with the first sale. Sources: State statutes; notices and guidance; Tax Foundation research. |

|||

| No Notch Effect | Notch Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Lookback | Future Sales | |

| Alabama | ✓ | ||

| Alaska | No remote seller requirement | ||

| Arizona | ✓ | ||

| Arkansas | ✓ | ✓ | |

| California | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Colorado | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Connecticut | ✓ | ||

| Delaware | No sales tax | ||

| Florida | No remote seller requirement | ||

| Georgia | ✓ | ||

| Hawaii | ✓ | ||

| Idaho | ✓ | ||

| Illinois | ✓ | ||

| Indiana | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kansas | * | ||

| Kentucky | ✓ | ||

| Louisiana | ✓ | ||

| Maine | ✓ | ||

| Maryland | ✓ | ||

| Massachusetts | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Michigan | ✓ | ||

| Minnesota | ✓ | ||

| Mississippi | ✓ | ||

| Missouri | No remote seller requirement | ||

| Montana | No sales tax | ||

| Nebraska | ✓ | ||

| Nevada | ✓ | ||

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | ||

| New Jersey | ✓ | ✓ | |

| New Mexico | ✓ | ||

| New York | ✓ | ||

| North Carolina | ✓ | ||

| North Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ohio | ✓ | ||

| Oklahoma | ✓ | ||

| Oregon | No sales tax | ||

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | ||

| Rhode Island | ✓ | ||

| South Carolina | ✓ | ||

| South Dakota | ✓ | ||

| Tennessee | ✓ | ||

| Texas | ✓ | ||

| Utah | ✓ | ||

| Vermont | ✓ | ||

| Virginia | ✓ | ||

| Washington | ✓ | ||

| West Virginia | ✓ | ||

| Wisconsin | ✓ | ||

| Wyoming | ✓ | ||

| District of Columbia | ✓ | ||

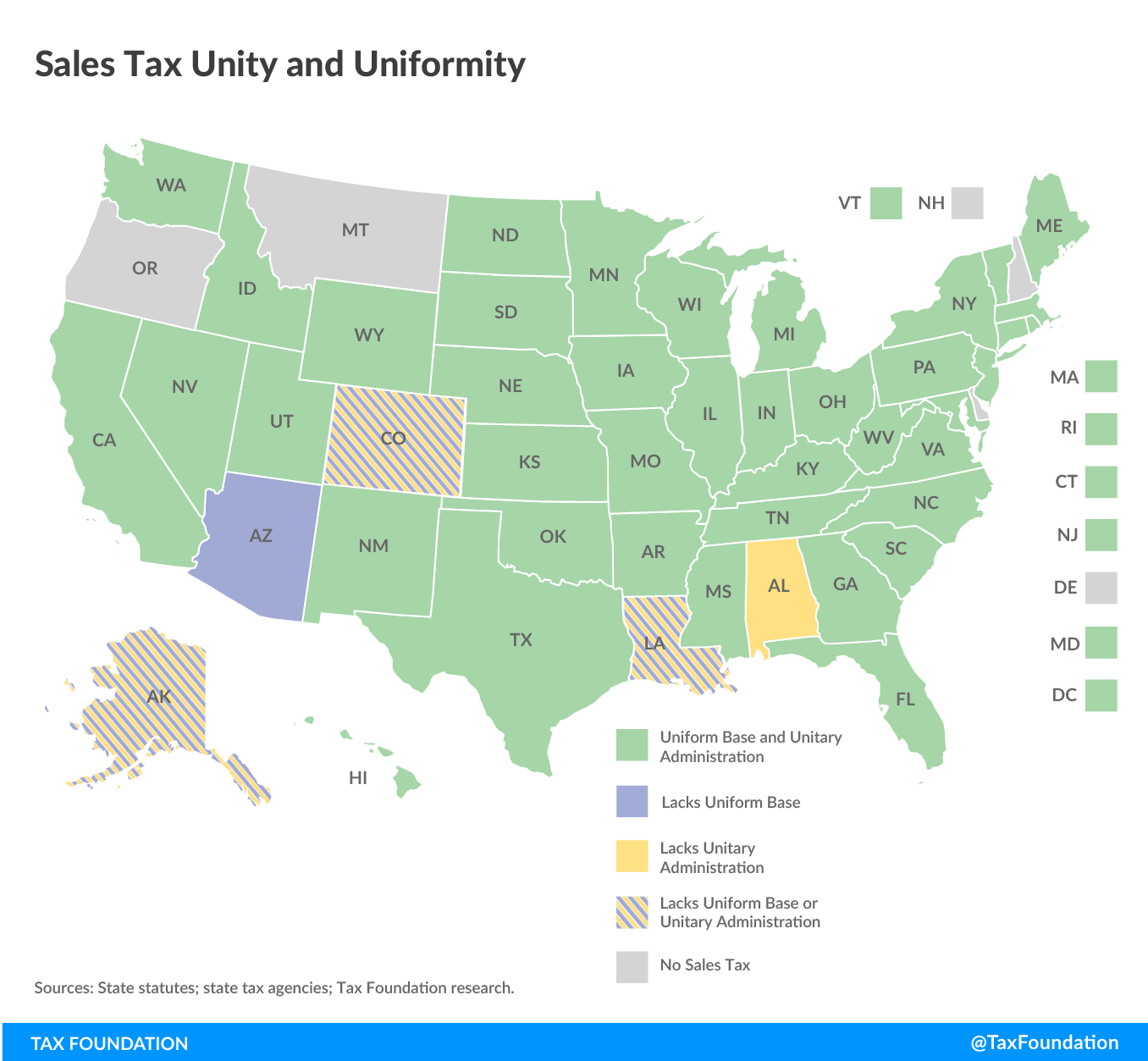

Embracing Unity and Uniformity

Simplicity in sales tax administration, or the lack thereof, has been an enduring concern of the Supreme Court since at least Bellas Hess. Although courts are generally reluctant to intervene in matters of state tax authority, a common thread in restricting jurisprudence is the concern that even non-discriminatory taxes on interstate commerce can create complexity and compliance costs beyond what is reasonable for businesses to bear. It has not escaped the Court’s attention that there are more than 10,000 sales tax jurisdictions in this country, and a state’s ability to mandate compliance by remote sellers is predicated on its ability to ensure that this multiplicity of jurisdictions does not impose too heavy a burden.

Despite some perplexing language in the Wayfair dicta about “simplified tax rate structures,”[30] it can be adduced from existing case law and the design of South Dakota’s own challenged law that states have little to worry about on this front if they have a single point of collections and administration, a uniform tax base, and a simple and reliable way to identify the appropriate local tax rate. When states fall short of these standards of unity and uniformity, however, they impose considerable costs on remote sellers, almost certainly reduce compliance, and likely run afoul of sellers’ constitutional protections.

Local sales taxes are imposed in 38 states—in Alaska, which has no state sales tax, and in addition to the state sales tax in 37 of the 45 states which impose one.[31] Local sales tax authority varies widely. In some states, only select jurisdictions may impose a sales tax, while in others, a broad range of jurisdictions—counties, municipalities, and various local authorities—may opt, either by ordinance or local referendum, to impose a sales tax. Generally, these local sales taxes are levied on the same base used at the state level, and collections and administration are centralized within the state’s revenue agency, with the local share remitted by the state collection authority. In many cases, moreover, states make it relatively easy to link a delivery address or coordinates with a local rate through free software solutions which can be used on a standalone basis or through their integration with a variety of third-party vendors. It is when states diverge from these standards that issues arise.

Four states—Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, and Louisiana—permit local sales tax administration. In Alaska, this is an outgrowth of the state’s decision to forgo its own sales tax but to grant the authority to localities; in the other three states, it stems from strong home rule traditions and constitutional grants of local taxing power. Alabama has a unified tax base, meaning that localities cannot make their own choices about what to tax and what to exempt, but many local governments handle their own tax administration, which would obligate remote sellers to remit separately to each jurisdiction. In Alaska, Colorado, and Louisiana, this issue is compounded by the additional challenge of divergent tax bases, where different jurisdictions tax different baskets of goods and services. What is taxed in one jurisdiction may be exempt in another.

Figure 3.

In Alabama and Louisiana, policymakers have adopted simplification regimes for remote sellers in response to these impediments, but the alternatives devised have their own constitutional infirmities. In Alabama, for instance, where the state rate is 4 percent but the average local rate is 5.16 percent, remote sellers pay a Simplified Seller Use Tax of 8 percent instead of remitting to each locality separately.[32] Since the simplified rate is lower than the average rate and eliminates the need to comply with the locally administered sales taxes in 59 of the state’s 67 counties and 275 of its cities and towns,[33] many remote sellers may be satisfied with this expedient. Some buyers may also be pleased; it is an excellent deal for a sale into Mobile, where the combined state and local rate is 10.5 percent, but far less equitable if the purchase is in tiny Saginaw, where the combined rate is only 5 percent. Indeed, in 189 jurisdictions—most of them quite small—the combined sales tax rate is less than 8 percent.

In those jurisdictions, taxpayers face a lower rate on an intrastate sale than they do on an interstate one, treatment which discriminates against interstate commerce. The Simplified Seller Use Tax contains a provision intended to mitigate the problem by allowing consumers to file for a refund of any overpayments, but this petition for refund—which can be filed no more frequently than once per year, must document all such transactions for which a refund is requested, and can only be claimed when the amount to be refunded exceeds $25[34] —imposes significant compliance costs on taxpayers who were excessively taxed.

Louisiana, similarly, has established a new Sales and Use Tax Commission for remote sellers to serve as a single collection entity, and a Uniform Local Sales Tax Board to promote (but not necessarily enforce) uniformity and efficiency in sales tax administration. The state has promulgated an alternative uniform 4 percent local sales tax rate. These efforts, however, are incomplete, and suffer from the same shortcomings that call Alabama’s approach into question. The Bayou State did, however, clean up one clear impediment to remote sales tax collections. As reported in The (Baton Rouge) Advocate, “Under the 5 percent state sales tax rate that lasted for 27 months, many transactions were taxed at different rates. For example, the state taxed Bibles at the full 5 percent, electricity for nonresidential use at 4 percent, new boats at 3 percent, new-car rebates at 2 percent and the sale of equipment used for manufacturing at 1 percent.”[35]

Colorado’s home rule jurisdictions also pose challenges, since those jurisdictions—like Louisiana’s, but not Alabama’s—are entitled not only to their own sales tax administration, but also to their own sales tax bases. No comprehensive matrix of local sales tax bases exists, and even a geographic mapping system identifying jurisdiction over different delivery addresses remains elusive. Although home rule jurisdictions have yet to press a claim to remote sales tax collections, the threat that they may do so looms. There is, moreover, the further possibility that remote sellers could, in some jurisdictions, be required to obtain business and seller licenses if they have nexus with the state and make even a single sale into the local jurisdiction. That would impose a burden substantial enough that it might conceivably give rise to a Pike balancing test case (discussed later), a possibility raised by the Supreme Court in Wayfair but often dismissed as too difficult a case to make.[36]

Additionally, Arizona and South Carolina allow certain local jurisdictions to diverge from the state sales tax base. South Carolina uses the state base for all remote transactions,[37] but Arizona does not. (Arizona only recently implemented central administration.) While the divergences are minor, Arizona municipalities tend, for instance, to tax fine art under certain circumstances, while the state does not, and municipalities vary in their treatment of various agricultural inputs, like the sale of breeding animals and livestock feed and medication.[38] It is easy to dismiss these divergences as trifles, at least for most taxpayers (though perhaps not those who make their living as farmers or ranchers), but there is no such thing as “close enough to constitutional.”

|

Sources: State statutes; state tax agencies; Tax Foundation research. |

||

| State | Uniform Base | Unitary Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | ✓ | ✗ |

| Alaska | ✗ | ✗ |

| Arizona | ✗ | ✓ |

| Colorado | ✗ | ✗ |

| Louisiana | ✗ | ✗ |

Missouri, one of two sales tax states yet to adopt a remote seller law, has more than 2,200 sales tax districts—not just municipalities and school districts, but ambulance districts, library districts, levee districts, and more.[39] At present, the state lacks any mechanism by which sellers could easily determine the taxes for which they are liable at any given address. To make matters worse, in some cases the use tax rate does not match the sales tax rate.[40] Unlike other states with significant local complexity, like Alabama and Louisiana, Missouri has chosen to proceed slowly, though it remains unclear if any simplification regime adopted in 2020 or subsequently will adequately address these impediments.

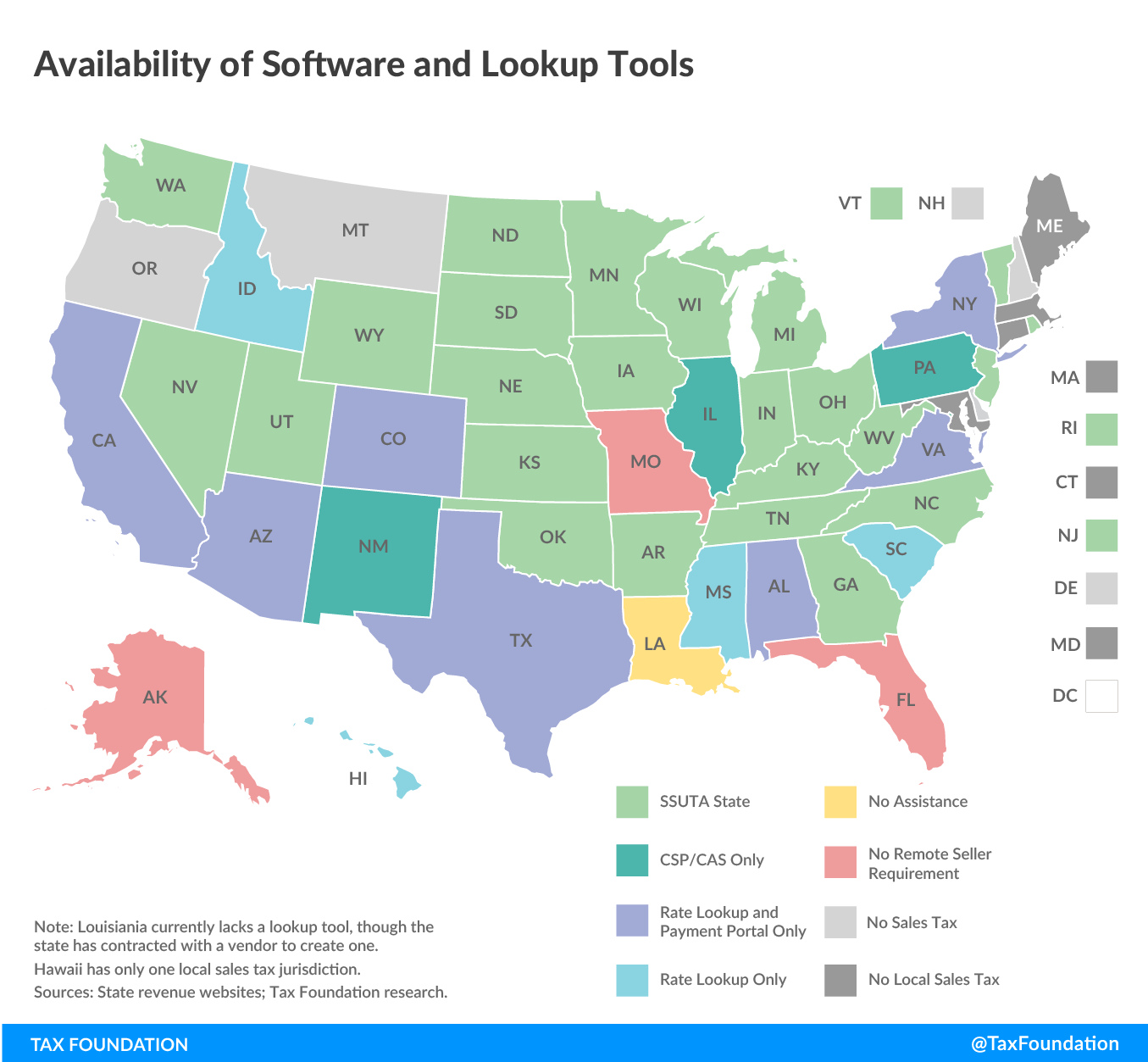

Providing Look-Up Software and Payment Portals

Even if local sales tax collection and administration is centralized at the state level and these taxes are imposed on a uniform base, sellers must be able to determine which taxing authorities have jurisdiction over each sale and what the appropriate local rate is. Absent some state-provided system, this can be unduly burdensome. If a business were obligated, for each sale, to determine which local sales tax authorities had jurisdiction over the delivery address—which might just involve identifying the county in which the address is located, but in some cases could also entail looking up school district, transportation district, soil and water authority, police and fire authority, and more—and what rate each imposed, this effort could quickly outstrip not only the amount of sales tax collected but also, in many cases, the profits made on the sale.

The Wayfair court acknowledged the legitimacy of this concern, particularly for small sellers, and expressed hope for a technical solution while observing that (1) if compliance proved untenable, Congress could act to impose certain requirements on states as a condition of their remote sales tax authority and (2) South Dakota and similarly situated states, particularly those party to the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SSUTA), provide free access to sales tax administration software and immunize sellers using that software from auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. liability for any errors arising from the software.[41]

The Court does not quite say that such a software solution is required, but the onus is on the state to find a way—presumably through software—to keep compliance burdens minimal. Occasionally, states with complex systems have protested that it is beyond their immediate capacity to map local sales tax jurisdictions or maintain a reliable database of local rates. But this is precisely the point: if it is an onerous task for state government, surely it cannot reasonably be expected of small out-of-state sellers. Many states have worked with so-called Certified Service Providers (CSPs), either independently or through the Streamlined Sales Tax Project, to offer software solutions.

Twenty-three states are members of the Streamlined Sales Tax Project and party to its agreement, which provides an effective way of both attaining and certifying these standards of unity and uniformity. These “Streamlined states” must, as a condition of membership, have a uniform base and a single point of administration, and accept limits on their ability to introduce rate complexity, though provision is made for varying local rates and reduced state rates on a few broad categories, like unprepared foods (groceries).

They also adopt common definitions, which should not be confused with common bases. A member state is free, for instance, to decide whether to tax or exempt “sport or recreational equipment,” “dietary supplements,” or “conference bridging services,” but those terms have the same meaning in all member states. A company selling recreational equipment must still determine whether a given state taxes that category of goods but can be confident that the same definitions and interpretations apply; they need not worry, for instance, that shin guards are classified as recreational equipment in one member state but as clothing or protective equipment in another.[42]

Importantly, the Streamlined Sales Tax Project facilitates software solutions, incorporating the sales tax regimes of all its member states into free software and working with six Certified Service Providers to integrate this information into the systems of commonly used sales tax compliance vendors. Sellers can either contract with one of those certified providers or use a freely available Certified Automated System (CAS), handling tax management on its own while using the same backend software available to the CSPs. This system interfaces with the seller’s accounting system to, according to the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board:

- Identify which products and services are taxable;

- Apply the appropriate tax rate;

- Maintain a record of the transaction; and

- Determine the amount of tax to report and pay to the Streamlined member states.[43]

Participating in the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement is an effective way to check many of the boxes of the “Wayfair checklist.” Unfortunately, many of the states with the largest economies remain holdouts.

Several non-Streamlined states, including Illinois,[44] New Mexico,[45] and Pennsylvania,[46] are working separately with CSPs to provide software sellers can use, and the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board is moving forward with a protocol whereby non-Streamlined states can join the Project’s central registration system. Finally, most non-Streamlined states do provide some level of assistance to sellers, typically in the form of online rate lookup tools and online payment portals, but these non-integrated systems can be quite burdensome to sellers, which must process each transaction manually.

|

* Hawaii only has one local sales tax jurisdiction. Sources: State revenue website; Tax Foundation research. |

||||

| Integrated Tools | Partial Solutions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | SSUTA | CSP/CAS Only | Look-Up Tool | Payment Portal |

| Alabama | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Alaska | No remote seller requirement | |||

| Arizona | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Arkansas | ✓ | |||

| California | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Colorado | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Connecticut | No local sales tax | |||

| Delaware | No sales tax | |||

| Florida | No remote seller requirement | |||

| Georgia | ✓ | |||

| Hawaii | ✓ | * | ||

| Idaho | ✓ | |||

| Illinois | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Indiana | ✓ | |||

| Iowa | ✓ | |||

| Kansas | ✓ | |||

| Kentucky | ✓ | |||

| Louisiana | ||||

| Maine | No local sales tax | |||

| Maryland | No local sales tax | |||

| Massachusetts | No local sales tax | |||

| Michigan | ✓ | |||

| Minnesota | ✓ | |||

| Mississippi | ✓ | |||

| Missouri | No remote seller requirement | |||

| Montana | No sales tax | |||

| Nebraska | ✓ | |||

| Nevada | ✓ | |||

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | |||

| New Jersey | ✓ | |||

| New Mexico | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| New York | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| North Carolina | ✓ | |||

| North Dakota | ✓ | |||

| Ohio | ✓ | |||

| Oklahoma | ✓ | |||

| Oregon | No sales tax | |||

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rhode Island | ✓ | |||

| South Carolina | ✓ | |||

| South Dakota | ✓ | |||

| Tennessee | ✓ | |||

| Texas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Utah | ✓ | |||

| Vermont | ✓ | |||

| Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Washington | ✓ | |||

| West Virginia | ✓ | |||

| Wisconsin | ✓ | |||

| Wyoming | ✓ | |||

| District of Columbia | Federal District | |||

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeFour states—Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina—currently lack a way to make central electronic payments, either through a CSP/CAS or an online portal, and Louisiana currently lacks a lookup tool (still necessary even with its simplified remittance regime), though the state has contracted with a vendor to create one.[47]

Figure 4.

Moving Past Physical Presence

Before the Wayfair decision established that economic presence could be sufficient for sales tax purposes, states adopted creatively expansive, if sometimes dubious, definitions of what constituted physical presence in an effort to cover a broader range of transactions.[48] These approaches, which were always bad policy, have no place now that states can adopt straightforward thresholds for remote sales tax obligations, and should be repealed.

Early efforts focused on broad definitions of “affiliate nexus” which determined a company to be physically present in the state if its vendors, sellers, or other businesses with which it had a contractual relationship were present in the state, but this overreach did not withstand legal scrutiny. An offshoot, often called click-through or referrer nexus (though sometimes still called affiliate nexus), deems a company to be physically present in the state if a referrer—someone who receives compensation for driving traffic or orders to the remote seller—is located there. This approach has had mixed success.[49]

Under this system, a seller was deemed physically present in a state if a paid affiliate or referrer resided there, most commonly an individual receiving commissions or credit for online sales driven by their ads or referral links. This extension of the sales and use tax came to be called the “Amazon tax” in some states due to its role in establishing nexus with the e-commerce giant, though other sellers were affected as well.

Interestingly, such solicitation of sales by non-employees is insufficient to establish nexus in a state for corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. purposes even though corporate income taxes generally attach on the basis of economic (not physical) presence nexus, due to the workings of federal law.[50] Nexus established by the use of unrelated third-party representatives to solicit sales in a state has, however, been upheld by the courts, though the case law is inconsistent, with the Supreme Court in one 1992 case holding that there must be a connection to both the actor and the activity the state wishes to tax.[51]

New York pioneered click-through nexus in 2008,[52] with other states following suit, typically with some de minimis threshold for click-through sales volume. Sometimes, however, these thresholds could be extremely low; Connecticut, for instance, set a floor of only $2,000 prior to the Wayfair decision and did not eliminate click-through nexus after adopting a post-Wayfair remote seller regime, though it did align the click-through threshold with its new safe harbor for economic presence nexus.[53] Eighteen states retain click-through nexus in their sales tax codes post-Wayfair, including populous northeastern states like New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, while six states—Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Ohio, and Washington—have repealed these provisions.

Another approach, less popular and more legally fraught, is known as “cookie nexus.” Internet users are familiar with cookies, small data files that websites store on users’ computers to retain information about the user and their online activity across internet sessions. Cookies are ubiquitous with online retailers, advertisers, and other popular online destinations, and Massachusetts latched onto the idea that these digital footprints, when stored on a user’s computer that was physically located in the state, rendered the retailer itself physically present and thus subject to collection and remittance obligations.[54]

Ohio and Rhode Island followed Massachusetts’ lead, but implementation of the Ohio regime was stayed by litigation and the law was repealed with the enactment of new post-Wayfair economic presence nexus laws without ever going into effect. Massachusetts also repealed its cookie nexus law post-Wayfair, but Rhode Island’s law remains in effect, as does a similar requirement in Iowa, which was adopted in tandem with its new economic nexus provisions.[55]

Finally, in the absence of physical presence, several states adopted notice and reporting requirements, requiring remote sellers to notify purchasers of their use tax obligations on transactions not taxed at the point of sale and, in most cases, further obligating the retailer to provide the state with an annual report of these potentially taxable transactions on which tax was not collected, providing revenue officials with a list of in-state buyers to check against the use tax they reported to the state.

Requirements for notice vary by state; it could be on the retailer’s website, specifically on their online shopping cart checkout page, or on the order confirmation, reminding the purchaser of their tax obligations. The reporting requirements are more uniform: remote sellers must, on an annual basis, provide these states with an accounting of the dates and amounts of each resident’s purchases. This has raised privacy concerns as, while retailers need not enumerate the items purchased, the information that a specific taxpayer has made a certain volume of purchases, or that those purchases have been with a particular seller, would usually be considered private and could, in some cases, prove damaging to the individual, disclosing health conditions, budgetary choices, and potentially embarrassing transactions.

Nine states impose notice and reporting requirements, with three allowing a remote seller to opt to collect and remit sales tax—even though the state lacks nexus to mandate it—in lieu of complying with the notice and reporting law, which can be costly and impose significant compliance burdens. Colorado’s notice and reporting law was struck down by a federal district court, which concluded that it imposed undue burdens on remote sellers, but the Tenth Circuit court reversed on appeal, and the viability of such laws is likely to be decided on the particulars of the requirements and any disparity of burdens on in-state and remote sellers, and not categorically.[56]

Hawaii, Pennsylvania, and South Dakota impose these requirements on all remote sellers not collecting and remitting sales tax, no matter how limited their activity in the state, making these laws particularly legally suspect. Rhode Island, South Carolina, and West Virginia repealed notice and reporting laws after the Wayfair decision.

|

* Only applies to companies with click-through nexus. ** Notice requirement only. Sources: State statutes; Tax Foundation research. |

|||

| State | Click-Through Nexus | Cookie Nexus | Notice and Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | ✓ | ||

| Alaska | |||

| Arizona | |||

| Arkansas | |||

| California | |||

| Colorado | |||

| Connecticut | ✓ | ✓* | |

| Delaware | No sales tax | ||

| Florida | |||

| Georgia | ✓ | ||

| Hawaii | |||

| Idaho | ✓ | ||

| Illinois | |||

| Indiana | |||

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kansas | ✓ | ||

| Kentucky | ✓** | ||

| Louisiana | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Maine | ✓ | ||

| Maryland | |||

| Massachusetts | |||

| Michigan | ✓ | ||

| Minnesota | ✓ | ||

| Mississippi | |||

| Missouri | ✓ | ||

| Montana | No sales tax | ||

| Nebraska | |||

| Nevada | ✓ | ✓* | |

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | ||

| New Jersey | ✓ | ||

| New Mexico | |||

| New York | ✓ | ||

| North Carolina | ✓ | ||

| North Dakota | |||

| Ohio | |||

| Oklahoma | ✓ | ||

| Oregon | No sales tax | ||

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rhode Island | ✓ | ✓ | |

| South Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | |

| South Dakota | ✓** | ||

| Tennessee | ✓ | ||

| Texas | |||

| Utah | |||

| Vermont | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Virginia | |||

| Washington | |||

| West Virginia | |||

| Wisconsin | |||

| Wyoming | |||

| District of Columbia | |||

| * Only applies to companies with click-through nexus. | |||

| ** Notice requirement only. | |||

States have been eager to move past physical presence and embrace economic presence nexus, but in doing so, they should eliminate these vestiges of the physical presence requirement. Click-through and cookie nexus, as well as notice and reporting requirements, are complex, inefficient, and in some cases legally doubtful workarounds to a problem that no longer exists, and states should not maintain them as a way to reach a certain subset of sellers which are below their new safe harbor thresholds. Their continuation breeds uncertainty and primarily burdens smaller sellers, since larger ones are almost invariably captured by the economic factors included in states’ post-Wayfair laws.

Figure 5.

Defining Facilitators with Intentionality

After expanding their sales tax collection and remittance obligations, most states shifted their attention to the next frontier: marketplace facilitators. A growing number of remote sales are facilitated by platforms and placing the burden on these facilitators rather than the sellers that use them confers multiple advantages. For the taxing state, it cuts down on administrative costs and extends obligations to sellers which would not exceed the safe harbor on their own; for sellers, it reduces compliance burdens by centralizing responsibilities in larger companies in a better position to handle the process.[57]

These platforms can take many forms. Although the quintessential example is an online storefront featuring products from many sellers—facilitators like Amazon Marketplace, eBay, and Etsy—other examples can include smartphone app stores (like the App Store or Google Play), delivery services (like UberEats and Postmates), and other sharing economy platforms.

Potential characteristics of marketplace facilitators include payment processing, fulfillment services, price setting, branding, and return assistance.[58] All but seven states with statewide sales taxes have enacted marketplace facilitator laws, and the rest are likely to follow, though states are still navigating the complexities of these provisions and statutes are likely to be tinkered with for years to come.

Marketplace facilitator laws make sense in this new tax environment, but sometimes the devil is in the details. If states are not careful, definitions of facilitators can be excessively broad, potentially capturing payment processors (including credit card companies) and others for which such laws were not intended and could impose obligations on multiple parties for the same transaction. Sometimes, moreover, a platform’s sellers might be better positioned to handle collection and remittance on their own, and a well-designed marketplace facilitation law would provide some flexibility in cases where platforms and their sellers both agree that the seller should assume responsibility for tax compliance.

Actual facilitation of the financial transaction is an essential, but not sufficient, condition in the definition of a platform. A company that merely sells advertising has no knowledge of any resulting sales and has no financial interaction with the consumer at which point it could reasonably collect the tax. These passive marketplaces, like Craigslist, Facebook Marketplace, or Google AdWords, never have a direct financial interaction with the consumer.[59]

Conversely, a pure payment processor does, in fact, handle the financial transaction, but has no knowledge of the sale terms: whether the purchased items were taxable, to which state they are sourced, and so on. Only when these two elements are combined—when a company enables a sale and handles the monetary exchange—is the facilitator in a position to collect and remit sales tax on behalf of the seller.

States which have adopted potentially overbroad definitions of marketplace facilitators have not, to date, attempted to enforce them against payment processors, advertisers, or others falling outside a more reasonable definition. However, overbroad laws create a conundrum for some companies, which must decide whether the letter of the law imposes some obligation on them, or whether, in practice, they are intended to be excluded from its reach.

It is possible, moreover, that a state could adopt a more aggressive stance in the future, perhaps to deal with foreign sellers over which it has no leverage. Imagine, for instance, that an international seller structures its business in such a way as to only sell into the United States, with no other activity here which might provide states with a means of enforcing remote sales tax obligations against them. In such a case, the state would be at the mercy of the judicial system of the company’s domiciliary country, which may or may not prove cooperative.[60] It could be tempting for states to seek other avenues for collecting this revenue, like shifting the obligation to a credit card company or other financial institution involved in processing the transaction. But while states might have a legitimate claim on the revenue, placing the onus on a third party is exceedingly arduous and constitutionally infirm.[61]

The Multistate Tax Commission (MTC) classifies states as having either narrow facilitator laws, limited to platforms that both list products or services for sale and process the transaction, or broad ones which are more nebulous in their reach.[62] Expanding this conceptual framework to all existing facilitator laws (the MTC has classified some, but not all), 20 states have adopted narrow definitions, while 18 have broad ones. Of particular concern, broad definitions could capture multiple platforms—for instance, an app store, a cell phone provider, and a credit card company—and theoretically obligate each of them to collect sales tax on the same transaction.[63]

States tend to use the same safe harbors for facilitators that they employ for individual remote sellers, though this need not be the case.

|

Sources: State statutes; Multistate Tax Commission; Tax Foundation research. |

||

| State | Safe Harbor | Facilitator Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | $250,000.00 | Broad |

| Alaska | No facilitator law | |

| Arizona | $100,000.00 | Narrow |

| Arkansas | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| California | $500,000.00 | Broad |

| Colorado | $100,000.00 | Narrow |

| Connecticut | $100,000 and 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Delaware | No sales tax | |

| Florida | No facilitator law | |

| Georgia | No facilitator law | |

| Hawaii | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Idaho | $100,000.00 | Broad |

| Illinois | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Indiana | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Iowa | $100,000.00 | Broad |

| Kansas | n.a. | Broad |

| Kentucky | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Louisiana | No law, but litigation | |

| Maine | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Maryland | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Massachusetts | $100,000.00 | Broad |

| Michigan | No facilitator law | |

| Minnesota | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Mississippi | No facilitator law | |

| Missouri | No facilitator law | |

| Montana | No sales tax | |

| Nebraska | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Nevada | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | |

| New Jersey | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| New Mexico | $100,000.00 | Narrow |

| New York | $500,000.00 | Narrow |

| North Carolina | No facilitator law | |

| North Dakota | $100,000.00 | Broad |

| Ohio | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Oklahoma | $10,000.00 | Narrow |

| Oregon | No sales tax | |

| Pennsylvania | $100,000.00 | Narrow |

| Rhode Island | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| South Carolina | $100,000.00 | Narrow |

| South Dakota | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Tennessee | No facilitator law | |

| Texas | $500,000.00 | Narrow |

| Utah | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Vermont | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Virginia | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Washington | $100,000.00 | Broad |

| West Virginia | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Broad |

| Wisconsin | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| Wyoming | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

| District of Columbia | $100,000 or 200 transactions | Narrow |

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeWhile platforms are better positioned to collect and remit sales tax than their affiliated vendors in most cases, this is not invariably the case. Consider, for instance, a sharing economy service providing grocery or restaurant pickup and delivery services. Compared to a grocer, the delivery service is ill-positioned to know what share of an order is subject to sales tax, since determinations of which foods are taxable and untaxed can be extraordinarily complex. A local meals tax, moreover, might fall on a restaurant or on prepared foods sold at a grocery store, and that tax is an excise tax that is origin-sourced, which is to say taxed where the seller is located, in contrast to sales taxes, which are typically destination-sourced, based on the location of the purchaser at the point of sale.

The point of sale is, in fact, a surprisingly complex issue with third-party delivery services. In some cases, typically where the delivery service has no official arrangement with the seller, the facilitator takes legal title to the product when it picks it up and pays for it, prior to delivery to the consumer. That makes the seller’s establishment the destination of the sale, and thus the jurisdiction to which any local sales tax should be remitted, while the destination for any fees imposed by the delivery service would be the location where the purchaser receives the goods (assuming delivery services are within the state’s sales tax base). Often, however, when delivery services cooperate directly with the restaurant or store, the products are not actually sold—title does not transfer—until the purchaser takes possession of them, meaning that the destination of the sale of the good (as well as of the delivery service) is the address at which the consumer takes possession. States have struggled to provide clear guidance on how sellers and facilitators should handle these complexities and ambiguities.

Meals taxes are but one example of excise taxes that might attach to the same purchase and introduce complexity into marketplace transactions. The telecommunications industry adds a further wrinkle, since telecom companies are responsible for a range of excise taxes on their services, which a third-party seller may not be equipped to handle.

Although it does not solve all problems raised by these competing obligations, states can enhance their marketplace facilitator laws by allowing facilitators and sellers to come to a mutual agreement about which one bears responsibility for collecting and remitting the sales tax. Several states allow contractual negotiations or have provisions waiving the requirement that the facilitator collect sales tax under certain circumstances or allow the revenue department to issue waivers,[64] with the National Conference of State Legislatures considering model legislation that would grant such choices to large sellers (with the cooperation of the facilitator) and in cases where a facilitator can demonstrate that essentially all of its sellers are already sales tax collectors.[65] Maine, Minnesota, and Nevada are examples of states with a collection responsibility determination, while Maryland, Massachusetts, Ohio, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin authorize waivers.[66]

Figure 6.

Getting the Small Stuff Right

The aforementioned issues dominate most considerations in extending tax obligations to remote sellers, but seemingly smaller concerns are also important. Thus far, no state has applied collection and remittance obligations retroactively, but doing so would be poor policy and invite a Due Process Clause challenge. Liability protection is important, both in the event of any errors arising from reliance on state-provided software and in cases where a seller or facilitator has good faith reasons to expect that the other is collecting and remitting, or where a facilitator relies on inaccurate information provided by a seller.[67] And what seems like mere semantics may also matter.

Throughout this paper, we have employed terms like “remote sales tax” in keeping with customary usage. Technically, however, what is collected by remote sellers tends not to be the sales tax but the reciprocating use tax. Sales taxes generally have transactional nexus—the transaction is conducted within the state’s borders—whereas use taxes are imposed at the point of consumption when individuals purchase a good or service elsewhere. South Dakota’s remote seller and marketplaces bills are drawn to its sales tax, not its use tax, and a few other states do likewise.[68] Whether such formalistic requirements still matter is uncertain,[69] but the safer course is to distinguish between sales and use taxes and apply economic nexus standards to the latter.[70]

Finally, the concept of economic nexus is rooted in the notion that sales and use taxes are destination-based, since the destination state is exercising its right to tax the remote transaction, yet some states use a mix of origin- and destination-sourcing, or even employ language that could result in double taxation. Tennessee considers a taxable sale to occur upon “any transfer of title or possession, or both” for which consideration is given, but with remote sales, it is possible for the transfer of title to be discrete from taking possession, theoretically giving rise to two separate taxable events—a Commerce Clause violation if actually enforced that way.[71]

Twelve states use origin sourcing for intrastate sales, and of these, only one (New Mexico) are consistent in also relying on it for remote sellers. Ten states use origin sourcing for intrastate sales but destination sourcing for interstate transactions: Arizona, Illinois, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia. Finally, California uses origin sourcing for state and municipal sales taxes on both intrastate and interstate commerce, but destination sourcing for sales taxes imposed by special districts. These states should take the opportunity afforded by their newfound post-Wayfair authority to better align their sales tax codes, moving to destination sourcing for all sales.[72]

Navigating the Law Around Remote Sales Tax Collections

Although the Wayfair decision resolved one vital question—that physical presence is not a necessary condition of nexus—it fails to provide much clarity on what does constitute nexus, or even which constitutional provisions govern that question. Largely considered a Due Process Clause concern prior to the 1992 Quill decision, Wayfair affirms that there are both Due Process and Dormant Commerce Clause inquiries, but appears to regard them as similar, if not nearly identical. Some argue that with the abandonment of Quill’s physical presence rule, nexus should once again be evaluated according to Due Process Clause principles.[73] The Court itself leaves the question unresolved, noting only that the Due Process and Commerce Clause standards “may not be identical or coterminous” though “there are significant parallels,” while citing the Bellas Hess proposition that the nexus requirement is “’closely related’ to the due process requirement that there be ‘some definite link, some minimum connection, between a state and the person, property or transaction it seeks to tax.’”[74]

Due Process standards are, by definition, procedural, concerned with notice, fair warning, and consequently an absence of (or limitation on) retroactivity.[75] Provided a company purposely avails itself of a state’s market, it should usually be in reach of a Due Process Clause-compliant remote sales tax regime. The Commerce Clause nexus requirement, as envisioned by the Wayfair Court, is not much different, requiring that the tax obligation apply to an activity with substantial nexus with the state.[76]

This, however, has a propensity toward circularity and tautology, with tax nexus attaching where an activity has substantial nexus. Legal scholars have suggested that the nexus standard question has two threads. The first is that of a company purposefully availing itself of the substantial privilege of exploiting a state’s market. Here, it is not the substantiality of the activity, but of the privilege, that matters. Provided that a company intentionally transacts business in the state, it likely meets the test, which is consistent with Due Process requirements. The second, better associated with the Dormant Commerce Clause, is the notion that the economic contacts in the state must themselves be sufficient, which forms the legal basis for providing a safe harbor to shield de minimis contacts.[77]

Notably, the term “substantial nexus” is more prominent in recent case law. In Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady, where the Supreme Court first established a four-pronged Commerce Clause test for interstate taxation,[78] the phrase “substantial nexus” was only used once, with the more nebulous “sufficient nexus” generally favored.[79] Without quite defining it, though, the Court has gradually embraced the requirement that nexus be substantial, which puts remote sales tax regimes like the one in Kansas, which lacks a safe harbor, in legal jeopardy.

Nexus is, however, only a threshold question. Assuming a company has sufficient economic contacts for the establishment of tax nexus, it is still possible that the features or effects of that tax regime could impose undue burdens on or discriminate against interstate commerce.[80]

Undue burden inquiries largely derive from a regulatory case, Pike v. Bruce Church, Inc., which has little history of application to taxes. The four prongs of the Complete Auto test are (1) substantial nexus, (2) nondiscrimination, (3) fair apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. , and (4) fair relationship to services provided by the state, and in a subsequent case, the Supreme Court indicated that a tax regime does not impermissibly burden interstate commerce if it is consistent with those four prongs.[81] Nevertheless, the majority opinion in Wayfair opens the door to the application of the “balancing test” in Pike to remote sales tax regimes (and other state taxes). Pike stands in opposition to the notion that any rational law that does not expressly discriminate against interstate commerce is constitutionally sound under the Dormant Commerce Clause, holding that some burdens on interstate commerce are too large to be justified.[82]